Congress is back in session and the HVACR industry is waiting to see what the Senate has to say about the Waxman-Markey bill, H.R. 2454 - the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 (ACES). The bill, which already passed in the House, contains sweeping environmental reform that will change the way this industry and America does business. Divided into five main sections, known as titles, it is Title III, “Reducing Global Warming Pollution,” that has the industry on alert. From this section of the current bill, the Safe Climate Act emerges, along with the reasons, regulations, and procedures for a carbon cap and trade program.

CAP AND TRADE SHORTHAND

Discussions on this topic began long before this bill made a serious play to become a law and the HVACR industry has been preparing itself for the coming changes. Although concerned about aspects of the climate legislation, the general industry is pleased that the Waxman-Markey bill employs a phase down and not a phase out of HFCs.“While HFCs are a greenhouse gas, it’s important to remember that they are needed substitutes for ozone-depleting refrigerants,” said John Mandyck, vice president, Sustainability and Environmental Strategies, Carrier Corp. “In chillers, for example, HFC-134a replaced CFC-12 to address the ozone problem while reducing the greenhouse gas impact by 80 percent. Now public policies are looking to reduce the greenhouse gas impact of HFCs further, even though we don’t have EPA-approved alternatives yet. Reduction schedules like those in Waxman-Markey will be a true test for technology and innovation beyond what we’ve seen before with refrigerants.”

The Safe Climate Act is the name given to Title III and sections 112, 116, 221, 222, and 223 of the Waxman-Markey bill. In the first section, global warming is defined as an eminent threat directly resulting from the combined anthropogenic (caused by man as air pollution) greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from numerous sources of all types and sizes. The Safe Climate Act states its overall purpose is to “help prevent, reduce the pace of, mitigate, and remedy global warming and its adverse effects.” To accomplish this goal, the Safe Climate Act - an amendment to the Clean Air Act, which was most recently amended in 1990 - is purposed to “establish and maintain an effective, transparent, and fair market for emission allowances and preserve the integrity of the cap on emissions and of offset credits.”

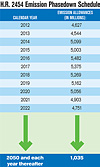

The intention is to cap overall U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 3 percent in 2012 as compared to the same emissions of 2005, and then incrementally reduce these reductions by 83 percent in 2050.

The following are defined as greenhouse gases: Carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, hydrofluorocarbons emitted from a chemical manufacturing process at an industrial stationary source, any perfluorocarbon, nitrogen triflouride, and any other anthropogenic gas designated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administrator.

The bill also provides a listing of the carbon dioxide equivalents of 1 ton of GHGs. Among them, HFC-134a would be equivalent to 1,430 metric tons of carbon dioxide. Along with the identification of the gases and their carbon dioxide equivalents, Sec. 713 establishes a climate registry and defines who is responsible to be a reporting entity.

“A covered entity would be a covered entity if it has emitted, produced, imported, manufactured, or delivered in 2008 or any subsequent year more than the applicable threshold level … and any other entity that emits a greenhouse gas, or produces, imports, manufactures, or delivers material whose use results or may result in greenhouse gas emissions if the Administrator [EPA administrator] determines that reporting under this section by such entity will help achieve the purpose of this title … any vehicle fleet with emissions of more than 25,000 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent on an annual basis if the Administrator deems this will help achieve the purpose …”

Having established this registry, reporting entities will be required to make a report to the EPA administrator for calendar years 2007-2010 no later than March 31, 2011. During this period, some waivers will be granted to compensate for inaccurate record keeping. Afterwards, however, for the calendar year 2011 and every year after that, quarterly data must be submitted no later than 60 days after the end of the applicable quarter.

Figure 1.

MANUFACTURER PROS AND CONS

Larry Kouma, director, Large-Tonnage Chiller Products, Johnson Controls Inc., is excited about this legislation. According to him, “It includes the proper focus on equipment efficiency - carbon dioxide emissions from power generation are 5 to 10 times the global warming potential (indirect) when compared to direct impact from refrigerant loss to the atmosphere.”He agrees that the phase-down plan is the right step, but is concerned with the phase down schedule being aggressive and challenging.

“Manufacturers for residential and light-commercial HVAC equipment are currently spending millions of dollars converting their products from HCFCs to HFCs,” explained Kouma. “It will take some applications moving to low global warming potential refrigerants, e.g., the automotive industry, but early projections identify possibilities for compliance with the phase down schedule maintaining adequate supply for applications without alternatives identified today. This legislation may provide the catalyst for objective code review to consider safe application of hydrocarbons and ammonia for comfort cooling applications.”

As manufacturers face this challenging phase down timeline, Trane is taking “the same balanced approach that we have held for decades.” Mike Thompson, director of Environmental Affairs, agrees that refrigerant alternatives such as carbon dioxide, hydrocarbons, and ammonia have proven to be adequate refrigerants in certain applications, but overall, Thompson says Trane believes that additional relief is needed in the early years of this legislation’s implementation.

“In most applications, we remain concerned with the energy efficiency of CO2; the ability to deliver safe systems with hydrocarbons without considerable loss in energy efficiency from safety mitigating actions, such as the addition of intermediate heat exchangers; and the ability to deliver safe systems with ammonia due to its toxicity and flammability.”

Another concern being raised as carbon credits are being discussed is fair competition.

“This proposed legislation will allow the largest refrigerant companies in the world to extend the effective lives of patents on HFC blends, because 90 percent of all allocation for HFC production and importation would be awarded to these few companies,” explained Gordon McKinney, vice president and COO of ICOR International Inc. “In general, the cost of purchasing and maintaining HVACR systems could become cost prohibitive for the average American.”

Figure 2.

OPPOSITES SPEAK UP

Debate ranges wildly around the Waxman-Markey bill and proponents like the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) claims that the average American household could save approximately $1,050 per household by 2020 and $4,400 per household by 2030. It also predicts that energy efficiency provision will create 770,000 jobs by 2030 and reduce U.S. energy use by 5.4 quadrillion Btu.“This would account for about 5 percent of projected U.S. energy use in 2020,” said Steven Nadel, executive director of ACEEE. “This analysis directly underscores the important contribution energy efficiency provisions make toward keeping the cost of a cap-and-trade program to modest levels due to reduced energy use and reduced need for expensive new power plants.”

The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) and the American Council for Capital Formation (ACCF) released a state-by-state analysis of the Waxman-Markey Bill revealing information much the opposite of ACEEE’s optimistic predictions. According to the high-cost numbers of NAM-ACCF’s study, if the bill is passed in its current form, the cumulative loss in gross domestic product (GDP) will be up to $3.1 trillion between 2012 and 2030; employment losses will range up to 2.4 million jobs in 2030; residential electricity prices will increase up to 50 percent by 2030; and gasoline prices will increase 26 percent per gallon by 2030.

“Policymakers may have the best of intentions when it comes to the environment, but it’s crucial that we compare the economic cost to the legislation’s actual impact on global GHG reductions,” said Dr. Margo Thorning, senior vice president and chief economist for ACCF.

“Considering that developing countries such as China and India have publicly stated they will not undertake similar emissions policies, there would be almost no global environmental benefits from the bill. Ultimately, this study shows that Waxman-Markey would significantly decrease employment and increase energy prices at a time when we can least afford it.”

The Waxman-Markey bill is still being debated on the Senate side of Congress. It is unclear at this time when a vote is to be taken, although many expect a vote sometime this month.

For more information, visit http://thomas.loc.gov, www.nam.org, or www.aceee.org.

Sidebar: New Codes

Beyond carbon cap and trade, contractors can be looking for changes in new and existing building codes. If passed, the current Waxman-Markey climate bill sets the baseline code for residential buildings as the 2006 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) published by the International Code Council (ICC); and for commercial buildings, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Standard 90.1-2004. It then requires measurable improvements from there, setting percent reduction targets for most structures, including existing buildings both residential and commercial.Not just for new buildings, Sec. 202 in the bill outlines a building retrofit program that applies to assisted housing, nonresidential buildings, public housing, and residential buildings; differentiating between a performance-based building retrofit program and a prescriptive building retrofit program.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administrator, along with the Secretary of Energy and the Director of Commercial High-Performance Green Buildings will define the standards for a commercial and residential national energy and environmental building retrofit policy to be known as the Retrofit for Energy and Environmental Performance (REEP) program. To accomplish this task, the administrator will rely primarily on using existing programs, including Energy Star® and the EPA Energy Star for Buildings programs.

Publication date:10/19/2009