Refrigerant transitions, such as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) replacing chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), get all the press.

And as hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs), hydrocarbons (HCs), and natural refrigerants are set to replace HFCs, their often-overlooked partners — lubricants — are rarely mentioned. As the industry prepares to adhere to government-

mandated refrigerant transitions, one question is repeated over and over: “Can I use my old lubricants with

new refrigerants?”

The answer (as is the answer to many questions in the refrigerant world right now) is, “There’s not one simple answer.”

READ THE FINE PRINT

At a recent ASHRAE meeting, Ed Hessell, senior technology manager and OEM liaison, industrial finished fluids, Chemtura Corp., and a member of ASHRAE technical committee 3.4 Lubrication, chaired a seminar titled, “Making the Commercialization of Low-GWP [global warming potential] Refrigerants a Reality.” Hessell said a key component of that reality is lubricants.

“When it comes to the commercialization of low-GWP refrigerants, we don’t hear much about lubricants,” Hessell said. “But, they’re a crucial component to any refrigerant transition, and we are once again moving to a whole new generation of refrigerants. There’s ultimately going to be a larger number and a greater diversity of refrigerants than we have ever seen before. The biggest question is, ‘Will we be able to use the same lubricants we’ve always used?’ The answer in many cases is yes, but in certain cases, either you can’t use the previous lubricant or it would be much more energy efficient both in terms of performance and reliability of the equipment to use a new lubricant.”

The question is a crucial one for refrigerant manufacturers, Hessell noted, because, as the refrigerant and oil are always mixed, the performance of any new refrigerant can be impacted by the lubricant being used. On the equipment side, manufacturers would like to be able to use a single lubricant for every compressor they build.

When working with brand-new refrigerants in brand-new equipment, the refrigerants and lubricants can be designed to optimize system performance. In retrofit applications, where a high-GWP refrigerant is replaced in a system already in the field, contractors should ensure the lubricant being used is compatible with and recommended for use with the replacement refrigerant.

THREE MAJOR FACTORS

From the standpoint of lubricant manufacturers, refrigerant transitions can present a difficult task that nevertheless must be made easy for end users.

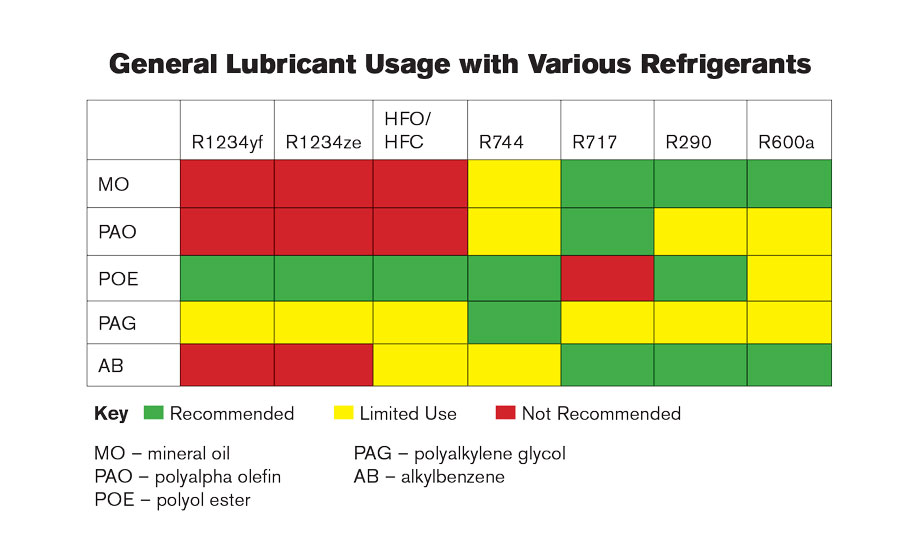

Joe Karnaz, global technology leader at CPI Fluid Engineering and chairman of ASHRAE TC 3.4, said lubricant manufacturers look at three major factors every time there’s a major refrigerant transition: miscibility, which is the interaction of lubricant and refrigerant in the system; solubility, which is the interaction of lubricant and refrigerant in the compressor that dictates the working viscosity the bearing will see; and compatibility or stability, which cover how the lubricant and refrigerant interact with each other and with other materials in the system.

“All of that has to be considered and reevaluated when we go through refrigerant changes,” Karnaz said. “You want to minimize the changes as much as possible. Minimizing change is better for system manufacturers, compressor manufacturers, and contractors. But, sometimes, things have to evolve into something new and different.”

Other factors that must be taken into account include the energy efficiency and reliability of the equipment.

“When you move to a low-GWP refrigerant, you might reduce the direct environmental impact of refrigerant potentially leaking into the atmosphere, but if the system has poor energy efficiency, you’re increasing the indirect environmental effects through increased energy consumption and the need for more generation from power plants,” he noted. “We have to look at all those factors.”

In addition, many compressor manufacturers are seeking increasingly sophisticated lubricant performance data before they begin designing and testing new equipment, and time to market is always a factor.

The good news for contractors and technicians is that the refrigerant and lubricant manufacturers work hard to minimize drastic changes, and whenchanges are needed, modern communication technologies will help everyone keep everything straight.

“Technicians today are certainly much more familiar with HCFCs and HFCs than they are with propane, carbon dioxide, and ammonia, but there’s also much greater access to information than ever before,” Karnaz said. “Thanks to the web and apps that will provide easy access to information from manufacturers, it’s possible it won’t be as big a leap to learn these things as it has been in the past.”

ALREADY A BIG STEP AHEAD

Steve Kujak, director of next-generation refrigerant research at Ingersoll Rand – Trane, pointed out that, from a lubricants point of view, the transition from HFCs to low-GWP refrigerants, such as HFOs, already has a big step up on the transition from CFCs to HFCS.

“The No. 1 technology issue going from CFCs to HFCs was that we didn’t have any lubricants compatible with the HFCs,” Kujak said. “So, a whole new chemistry of lubricants had to be developed. That took some time, because it can take five to 10 years to develop a new molecule, get approval from the regulators, create manufacturing processes, and so on.”

The two primary lubricants that emerged were polyolesters (POEs) and polyvinyl ethers (PVEs), both of which (in particular, the POEs) are compatible with new HFO refrigerants.

That’s not to say this transition isn’t without its challenges, Kujak noted. This time around, it’s the flammability of the refrigerants. Some of the low-GWP refrigerants, including the HFOs R-1234yf and R-1234ze as well as R-32, are classified as mildly flammable (class A2L) by ASHRAE.

“The industry is still working on new standards and trying to determine how the equipment may or may not need to change when using these mildly flammable refrigerants,” Kujak said.

Historically, mineral oils are typically used for HCs. “I see some people are starting to use POEs with HCs,” Kujak said. “The reason is mineral oils tend to look like HCs and they like to dissolve in each other, so you get lower viscosities. POE helps maintain the viscosity by reducing solubility of the HCs.”

Although some people have tried polyalkylene glycol (PAG), POEs are generally the oils of choice for systems that use carbon dioxide (CO2) as their refrigerant, according to Kujak. Ammonia is a unique animal, Kujak said, as there are few miscible oils used with ammonia. Most ammonia systems will use an alkyl benzene lubricant, which is immicible and must be used in a system equipped with an oil separator.

A CHANCE TO IMPROVE PERFORMANCE?

The seminar’s final speaker was Laurent Abbas, manager, research and development, global applications development and technical support, fluorochemicals, Arkema Inc. He said, during testing to ensure the new low-GWP refrigerants containing HFOs are compatible with the existing lubricants used with HFCs, it was discovered it may actually be possible for lubricants to help improve the performance of a system.

“The first thing we found was existing lubricant technology can do the job with the new refrigerants, so we don’t need to create a new technology or a new class of lubricants,” Abbas said. “But, we also found if you pick the right lubricant, you can improve a system’s performance.”

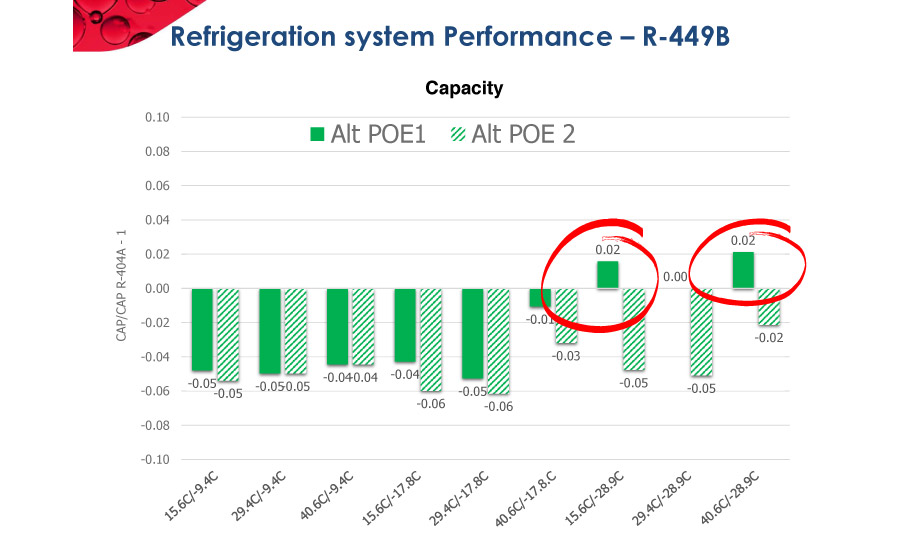

Abbas noted that the lubricant is in contact with refrigerant at all times and plays a thermo-fluidic role in the system, which can impact both system capacity and coefficient of performance.

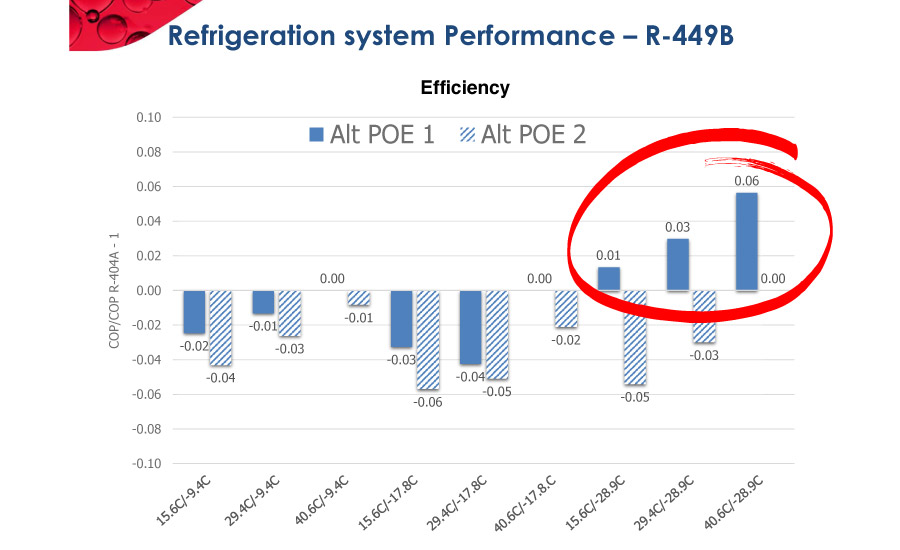

Researchers at Arkema, he explained, were studying lubrication properties of R-449B, a nonflammable replacement for R-404A with a GWP of 1,296. After finding that the existing POE lubricant used with R-404A was also a good lubricant for R-449B, Arkema continued testing with slightly different POE formulations.

All of the testing was done on an R-404A, 1-hp, walk-in freezer with matching evaporator and a reciprocating compressor.

“We kept the same refrigerant, R-449B, and we tested it with three different types of POE lubricants ranging from fully miscible to not miscible at all,” Abbas said. “We were pleased to find that, depending upon the operating conditions and the lubricant, we could end up with better system performance than what we saw with the standard lubricant.”

The performance difference was high enough to merit attention and further study going forward, Abbas said.

“The message to contractors and technicians is that work and research is going to continue behind the scenes to optimize low-GWP refrigerants and their lubricants,” he said. “We have always talked about the lubricant as a problem — that is, if you don’t pick the right lubricant, you’ll lose performance. We don’t often get the chance to talk about lubricants as having the potential to improve system performance.”

KEEP GOING TO THE GO-TOS

Hessell concluded that, while mineral oil was the lubricant of choice in the CFC era, that changed in the 1990s as the move was made to HFCs. Since then, POEs have been the go-to lubricant for systems that use HFCs and HFOs. That is likely to remain the case, even as research into new synthetic lubricants is ongoing.

“There may be some select cases where contractors will see new lubricants, but there likely won’t be major changes,” Hessell said. “From a contractor’s perspective, it will be just another POE oil in a can that has a different label on it. The good news is there’s probably not going to be big changes for contractors in what’s needed to install or maintain the equipment.”

Publication date: 7/4/2016

Want more HVAC industry news and information? Join The NEWS on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn today!