Since the COVID-19 pandemic hit North America last February, building IAQ has come into an entirely different focus. A flurry of virus safeguards have been added to commercial building indoor air quality (IAQ) strategies. Now the question arises whether one safeguard is enough.

The most popular strategies for mitigating airborne pathogens have been outdoor air dilution, various media filter improvements ranging from MERV 13 to high efficiency particulate arrestance (HEPA), off-hours building purging, ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI), and ionization. Building operators frequently choose one of the above methods; however, the question arises whether a better strategy is to combine two or more methods. A better building environment might be established by employing any of the above methods and then supporting it with outdoor air increases for dilution. The reasoning is based on the fact that most methods can stop working due to equipment failure, poor maintenance, or human intervention errors.

Indoor air dilution via increased outdoor air induction through HVAC systems is perhaps the most promising strategy. COVID-19 is replicated indoors; therefore, why not exhaust it outdoors and let Mother Nature mitigate it? Then bring in outdoor air that’s naturally disinfected from the sun’s ultraviolet rays, according to Acting Under Secretary William Bryan of the U.S. Dept. of Homeland Security’s research and development arm, the Science and Technology Directorate (STD).

The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), Federation of European Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning Associations (REHVA), and the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) recommend increased outdoor air, because that means air that possibly contains aerosolized disease particles is moved away from occupants and ideally exhausted outdoors. Clean, disinfected outdoor air replaces what was exhausted. A failure of this strategy could only be due to a malfunction of the building’s HVAC system, which would most likely prompt an occupant evacuation until ventilation is restored, regardless of a pandemic. Therefore, an outdoor air equipment failure probably wouldn’t go unnoticed and could be considered as a safeguard against poor IAQ.

Unfortunately, the other methods can go unnoticed. Filtration of all kinds can potentially fail or at least degrade over time, leaving the occupants unprotected from the target contaminant(s) it was installed to eradicate.

UVGI lamp technology in HVAC units or ductwork, for example, is a proven strategy for inactivating viruses. Two recent studies have proven its effectiveness against SARS CoV-2, which causes the disease COVID-19. A June 2020 study from Italy, “UV-C Irradiation is Highly Effective in Inactivating and Inhibiting SARS CoV-2 Replication,” (PDF) demonstrated inactivation to a virus density comparable to that observed in SARS CoV-2 infection. A UV-C dose of just 3.7-mJ/cm2 was sufficient to achieve a 3-log inactivation and complete inhibition of all viral concentrations was observed with 16.9-mJ/cm2.

Click diagram to enlarge.

While UVGI is proven against viruses, namely SARS CoV-2, its inherent degradation by up to 60% in just a two-year period can be detrimental. A degraded or burned out UV-C lamp that isn’t replaced will leave occupants unprotected from the building’s proactive strategy of UV lamp disinfection in the first place.

The same plays out with other technologies, such as ionization, which uses an electronic charge to create a plasma field filled with a high concentration of positive and negative ions. As these ions travel with the air stream, they attach to particles, pathogens, and gases. The ions help to agglomerate fine sub-micron particles and make them filterable. Furthermore, the ions kill pathogens by robbing them of life-sustaining hydrogen. The ions break down harmful VOCs with an Electron Volt Potential under twelve (eV<12) into harmless compounds like O2, CO2, N2, and H2O. The ions travel within the air stream into the occupied spaces, cleaning the air everywhere, even in spaces unseen.

The downside is that maintenance, especially periodic cleaning of the ionization bristles, is key to the technology’s effectiveness.

Likewise, improving media filtration from MERV-8 to MERV-13, which is recommended as potentially helpful in entrapping contaminated airborne aerosols and some sub-micron particles, can also be unintentionally sabotaged from replacement schedule voids. The same applies to HEPA, but in that instance, a dirty HEPA filter may seriously cause a blocked ventilation system.

The point of these examples is that filters, air cleaners, and other HVAC-related contaminant mitigation aids aren’t foolproof. However, if combined with outdoor air dilution equipment, such as energy recovery ventilators (ERV) or dedicated outdoor air systems (DOAS), the protection and assurance are doubled. Both technologies can work together toward the goal of mitigating a space’s virus, such as COVID-19. Furthermore, if the supplemental technology fails, outdoor air dilution can still protect occupants.

Precautions of ERV Use during a Pandemic

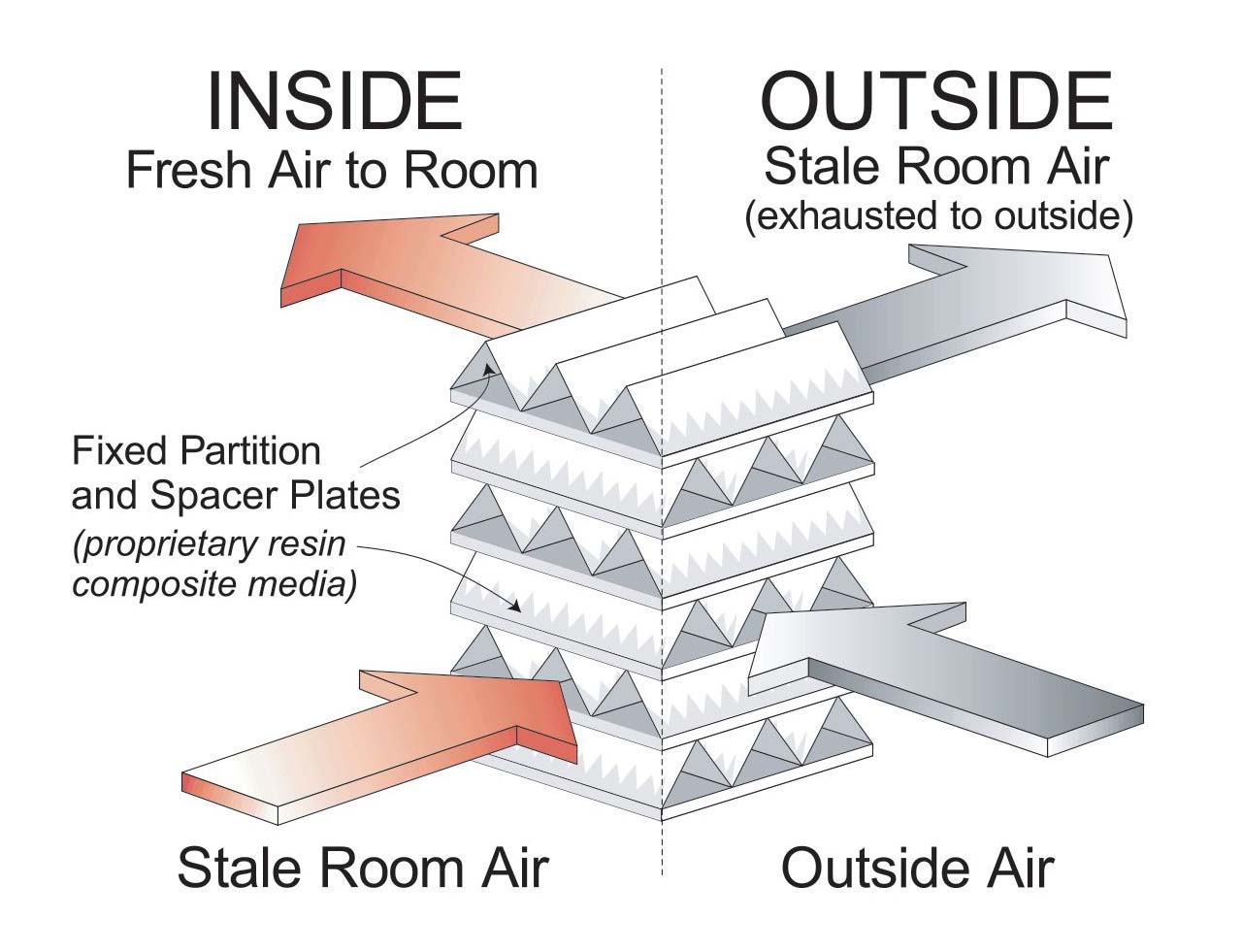

Generally, ERVs extract heat from the exhaust air and transfer it to the supply air. This handles both latent and sensible loads and allows more outdoor air without overdriving the air conditioning units’ cooling capabilities. ERVs can be applied as supplemental outdoor air units to existing AHUs, both separately or connected to the AHU itself. Depending on the size, configuration, and number of ERVs, any building with a conventional RTU can be converted to 100% outdoor air.

Since IAQ equipment failure is not an option during a pandemic, ERV selection becomes critically important. However, not all ERV equipment is the same. There are several methods of air-to-air ERVs; the most popular are energy wheels and static plate (enthalpy cores) heat exchangers.

Energy wheels are mechanical and depend on belts or gears, a motor, and a drive, all which need periodic maintenance. Static plate cores have no moving parts, only needing filter changes and annual core face vacuuming.

Click diagram to enlarge.

Depending on the method and their capabilities, ERVs can be a boon for mitigating a building’s COVID-19 potential (PDF), but they can also do more harm than good if they leak contaminated return air into the supply air during thermal transfer, which is called the Exhaust Air Transfer Rate (EATR).

Energy wheels without purge capabilities, for example, should not be used during pandemics, because of their potential for cross contamination. However, higher priced wheels with purge modes, triple seals, and other features can minimize cross contamination when correctly calibrated. Rotary heat exchanger leakage may occur if not properly installed. The most common fault is that the fans have been mounted in such a way that higher pressure on the exhaust air side is created. This will cause leakage from extract air into the supply air. The degree of uncontrolled transfer of polluted extract air can, in these cases, be up to an unacceptable 20%. If energy wheels can’t reach a near-zero cross contamination rate, or have solid seals to eliminate bypass between the wheel substrate and the HVAC system, they should not be operated during a pandemic (PDF).

Contrary to the energy wheel concept, static plate enthalpy cores keep air streams separate, according to AHRI Standard 1060, “Performance Rating of Air-to-Air Exchangers for Energy Recovery Ventilation Equipment,” which is used to certify equipment. Static plate enthalpy cores offer near-zero percent cross-contamination when operating with a properly balanced airflow. Instead of the energy wheel strategy of rotating through the supply and return airstreams with the same media, static plate technology completely separates the return air from the supply air during the energy exchange process. Many models have a leakage rate of 0.1%. REHVA backs this up with a recent position paper that stated “virus particle transmission via heat recovery devices is thought not to be an issue when an HVAC system is equipped with a twin coil unit or another heat recovery device” for separating return and supply side air stream.

Since static plate systems are tested and rated as near-zero cross contamination, their EATRs are significantly better than wheel technology. However, seals around the plates could have been installed incorrectly or aged in older HVAC systems. Therefore, seals need examination if the static plate-style ERVs are used during a pandemic.

Building IAQ has come into an entirely different focus since the pandemic. The question arises whether one safeguard is enough. While some technologies can adequately provide safe IAQ individually, adding other methodologies, especially the reliability of outdoor air dilution, can create safeguards to keep occupants healthy during this and future crises.

The bottom line is that ventilation is still the best solution for mitigating contaminants in occupied buildings. However, if the air conditioning system can’t handle the additional outdoor air’s heating or cooling loads, then an ERV is perhaps the best way rectifying that shortcoming.