There is no question that smart homes are the cutting edge in today’s residential technology. According to Security.org, about 32% of U.S. households had smart home technology in 2020, and that is expected to hit 57% by 2025. Now the headliners have moved from devices to entire smart home ecosystems, like LG’s ThinQ Home (unveiled in 2020) with its smart wine cellar, voice-controlled moving walls, and all-in-one app that serves as a remote control for everything from HVAC to TV to washing machine.

Seventy years ago, cutting-edge home tech was central air conditioning, and the proving grounds for this innovation was a 22-home experiment in Allendale, a subdivision in the northwest suburbs near Austin, Texas: the Air Conditioned Village. Like the smart home systems of today, the goal was in-home comfort, made for the masses.

Testing Modern Air Conditioning

Window a/c units had been in widespread use since the 1930s. But up until the 1950s, central air conditioning was typically found only in commercial buildings and high-end homes, largely due to cost of installation.

MADE FOR THE MASSES: The Air Conditioned Village was built specifically for middle-class buyers with the goal of testing how average Americans responded to central a/c in the home. (Courtesy of Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

As reported by the Austin Historic Landmark Commission, the Air Conditioned Village was specifically designed as a neighborhood of moderately-sized yet technologically-advanced houses with a price tag for middle-class buyers. Its goal was to test whether building homes with central a/c for the general public was affordable and feasible.

The Air Conditioned Village was built as a typical new-construction subdivision, with houses in various styles and with features popular in the postwar era: think single-story ranch design, deep eaves, and attached carports. All were in the range of 1,400 square feet — typical for middle-class neighborhoods in Austin at the time — and cost around $15,000, or about $150,000 in 2021 dollars.

Construction began in 1953 and was sponsored by the National Association of Home Builders. All the homes had central air conditioning furnished by a variety of manufacturers including Westinghouse, Coleman, Carrier, Frigidaire, American Standard, Lennox, General Electric, and Chrysler.

In addition to being outfitted with central air, the houses were deliberately designed to operate efficiently. Attics, kitchens, and bathrooms were ventilated. Windows were positioned to avoid strong sun. Insulation (a novel concept in the South at that point) was used in walls, and roofs had overhangs and carports to create more shade. Contemporary journal House & Home gushed that the houses had “practically every type of cooling equipment, air-distribution systems, insulation, and shading device.”

BUILDING A MOVEMENT: One big concern for the builders was that the a/c equipment would be too noisy and unsightly for a residential setting. Many took pains to hide it with partition walls. (Courtesy Of Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

According to the Austin Public Library, a big concern for the builders was that the equipment would be too noisy and unsightly for a residential setting. Not knowing that an a/c unit out back would one day be standard for American homes, many took pains to hide the equipment with partition walls.

The homes were named for the a/c equipment each featured: “The Air Temp House,” “The Weathermaker,” “The Cool Living,” “The Western Komfort,” and “The Comfortmaker.”

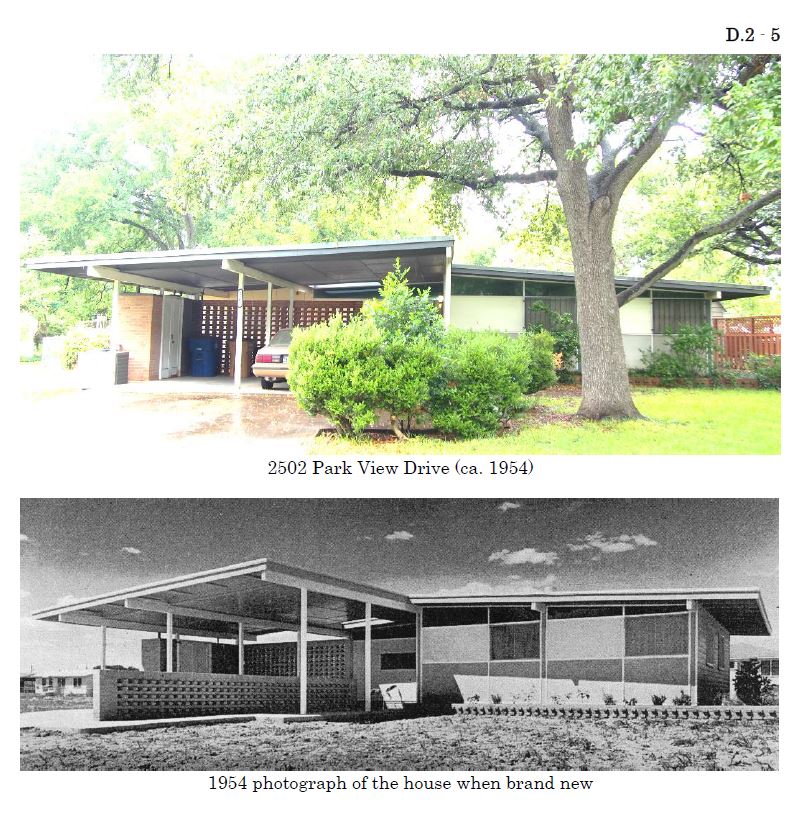

AIR TEMP HOUSE: Homes at the Air Conditioned Village were named for the a/c equipment each featured. These photos show the Chrysler “Air Temp” house, located at 2502 Park View Drive.

As with many high-profile projects, manufacturers jumped on the chance to get some free publicity for their housing products — about 30, to be exact.

“Other types of companies were equally eager to tout their products’ use in the Air Conditioned Village; these ranged from cabinetry (by Curtis Woodwork) to interior doors with built-in vents for air circulation (Amweld) and accordion-style wall partitions (Modernfold Doors),” reports the Allandale Neighbor.

A Social Study

The Air Conditioned Village was part economic feasibility study and part social study, with homeowners agreeing to the terms of the experiment when they purchased the houses. For one cooling season and one heating season, the houses and the families in them served as a field laboratory. Each house had a separate electric meter for the a/c unit so that operating costs could be recorded and analyzed by engineers. Plus, as reported by House & Home in August 1954, everyone in the experimental houses agreed to have their homes open one day a week to “qualified observers.”

Apparently, the little neighborhood drew quite the crowd.

“The Air Conditioned Village project was quite well known; its visitors even included a group of 10 housing experts from the Cold War-era Soviet Union,” the Allandale Neighbor noted.

Researchers studied air conditioning usage by the families to determine the efficiency and cost-benefit ratios of central air conditioning on a modest residential scale. The research included comparisons of energy costs, determining whether central air conditioning made sense for a typical middle-class budget, and looking at peak usage times and the demands on the city’s electrical grid. It also aimed to examine how year-round a/c would affect family life, according to a 1955 article in Texas Architect — things like whether children would eat better, whether people still wanted to open the windows, and whether a/c helped alleviate symptoms for people suffering from allergies.

The Results

After a year, the study concluded and published the results: People liked the air conditioned homes.

Among the reported quality-of-life improvements for families of the Air Conditioned Village were less dust and dirt in the home, more hobbies, and spending more time together as a family. Better sleep was another big one, with 19 of 20 respondents answering “yes” to “Do you awake rested?”

“They reported that families spent more time at home, slept longer, and were happier,” wrote Nicole Davis for the Austin Public Library. And while a few of their claims would raise an eyebrow today (better appetite with zero weight gain, anyone? — remember, this was the era when cigarettes were ‘physician tested’), the results clearly demonstrated what anyone living in Texas without a/c could testify: Any inconvenience of an air conditioner firing up paled in comparison to the benefits of a comfortable home environment.

And America agreed. The ACHR NEWS’ own coverage of the trend toward residential a/c stated that, as of May 1960, 27% of consumers were planning to buy an air conditioner.

“Soon after the experiment at Austin, the standard definition of the middle-class family would include owning a washing machine, a two-car garage, and ‘central’ air conditioning,” reports an article on the Air Conditioned Village in Cabinet. “By 1962, almost 6.5 million homes in the US, 60% of hotel rooms, and half of all office buildings were air-conditioned. A new design prophecy was spelled out.”

Today, most of the original Air Conditioned Village homes are still standing and in use as private residences — albeit with modern HVAC. The last original system was upgraded around 20 years ago.

While they might look inconspicuous to passers-by, so great was the impact of these little ranch houses that the Austin Historic Landmark Commission has even discussed designating them an official historic district, preserving them as a monument to the American story.

Which begs the question: Decades from now, will smart homes be so commonplace that LG’s ThinQ Home will be viewed as a historic landmark, too?