Two years ago, the sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic catapulted indoor air quality into the spotlight, launching HVAC terms like filters, air changes, IAQ, and UV from building and maintenance protocols to part of everyday life, news, and popular culture.

What will happen to IAQ enthusiasm when the pandemic has faded? Will people still be motivated to invest in IAQ if it means higher costs? Speaking in a November 2021 ASHRAE Journal supplier webinar titled “IAQ Control for Healthy, Resilient, Low Energy Buildings,” William Bahnfleth, Ph.D., P.E., said the groundwork has been laid for IAQ and energy efficiency to move forward hand in hand.

Bahnfleth is a fellow of ASHRAE, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, and the International Society for Indoor Air Quality and Climate. He served as president of ASHRAE in 2013-2014 and currently chairs the ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force.

“We're now at a point where there's a lot of motivation to make some significant changes in how we control indoor air quality and call them ‘revolutionary’ changes. But I don't want to say revolutionary in the sense that we have to wait for a new generation of technologies,” Bahnfleth said. “The first thing we have to do is simply change our minds about what our goals are. Reconciling the goals that we have around IAQ and our environmental goals has always been a barrier, but it doesn't need to be.

“I think the biggest problem we have here is siloing between energy and IAQ communities,” he continued, “and if they would work together, we could probably solve all of the problems in a better way and faster. So if we set new goals for health, resilience, and sustainability, we're going to be able to go a long way towards meeting them. The existing technologies and emerging technologies will only help support successful implementation.”

Raising the Minimum

Bahnfleth talked about what needs to happen for America to hit the twin goals of IAQ and energy efficiency in buildings.

COVID-19 has shown that current standards for acceptable indoor air quality are not sufficient, he said — evidenced by the fact that existing protocols were not enough to keep people safe without additional measures. Once the pandemic subsides, America shouldn’t go back to what was proven to be inadequate.

“I believe there’s a strong case for raising the minimum,” Bahnfleth said. “It's time to really get serious about doing something and changing our definition of what's acceptable. And I think one part of this is changing from ‘health’ as preventing disease to ‘health’ as promoting wellness and taking on board some of the healthy building concepts that we were already discussing before.”

The second part of this improved definition, he said, is resilience — not only with respect to airborne infectious disease, but also with disasters like wildfires, when outdoor air becomes completely unsuitable for ventilation.

Click to enlarge

RESILIENCY: Bahnfleth said “acceptable” IAQ needs to be resilient and able to adapt as needed — not only with respect to airborne infectious disease, but also with disasters like wildfires, when outdoor air becomes completely unsuitable for ventilation. (Courtesy of ASHRAE Journal Webinar)

“On the other hand, we can't operate our buildings like spaceships all the time, so that they don't require any outdoor air, and we don't want to run buildings like hospitals or bio labs because of the wasted energy that would result when we don't need that level of protection,” he said. “So resilience implies the ability to adapt when necessary. It needs to be balanced with sustainability — and then my response is that IAQ is part of sustainability.”

That does come with a caveat.

“It’s important that we don't misunderstand this message that we should strive for better indoor air quality,” Bahnfleth continued, “to mean that we should compromise or ignore our goals for energy and emissions.”

Nearly half the total energy used in running a typical building is associated with either the thermal environment or with controlling air contaminants, he pointed out. That is where sensors come into play, measuring air quality and occupancy so that IAQ efforts can be more targeted and efficient.

“You can't manage what you don't measure. That's still true today,” he said. “We probably need more sensing in most buildings than we have, and we need to do something useful with those signals. So that's one step in the right direction.”

Combination Cleaning

Combining ventilation, filtration, and air cleaning will be the key to low-energy, high-performance, high-IAQ buildings of the future, Bahnfleth said.

“Well, we need some ventilation,” he added. “I think the myopic focus on ventilation as the way to control indoor air quality is something that's holding us back. There's some places where air quality is almost always bad outdoors. There can be huge energy costs associated with increasing outdoor air, whether it's a cold climate in the winter or a hot/humid one in the summer, and then it costs further energy to distribute air throughout buildings in large quantities. It’s not always the best solution.”

That’s not to diminish its importance, though — or its popularity.

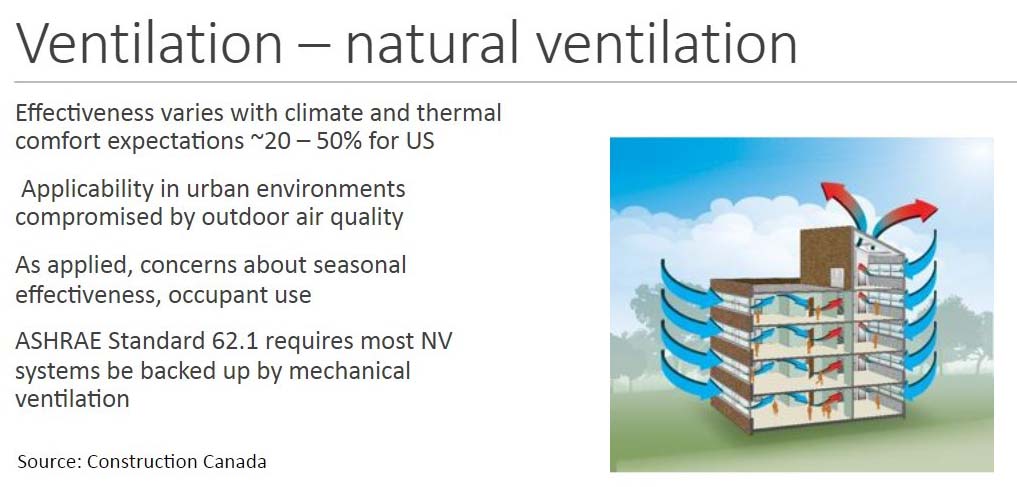

“Ventilation is going to continue to be a widely used way of controlling indoor air quality. So we need to make sure that results in as little energy use as possible,” he said. “So using hybrid ventilation where we can, or a natural ventilation hybrid, air to air recovery, more and better demand-control, economizers, dedicated outdoor air supplies, and better air delivery are all things that can help.”

Click to enlarge

ALL NATURAL: Natural ventilation could be one solution to provide both higher IAQ and lower energy use. It’s common in other parts of the world although not widely used in the U.S. (Courtesy of ASHRAE Journal Webinar)

Mechanical filtration and air cleaners to target specific contaminant classes can help get more control of indoor exposures without using so much energy, he said — hence, the need for more sensors that can measure and distinguish between particles, gases, and microorganisms. Moving from MERV 8 to MERV 13 as standard filter size would also be “a big step forward,” he said.

Improved ventilation, filtration, and air cleaning, plus sensing and controls, will make buildings more resilient because they can be adapted to whatever situation is at hand. Bahnfleth cited two examples: epidemics and wildfires.

“Epidemic disease outbreaks are something that we need to be able to combat better in the future than we have in the last two years. That might mean the ability to increase ventilation without disrupting operations, increasing the circulation through higher-efficiency air cleaners and the ability to deploy and operate additional air cleaners,” he said. “If we made some allowance for that in the design of buildings, we wouldn't still be trying to figure out what to do, in many buildings, 18 months after the pandemic started.”

For wildfires, the issue is protecting the outdoor air supply in the building — the DOAS — for ventilation. That may take both particulate and gaseous air cleaning, he said, adding that a guideline committee within ASHRAE is developing guidance on that specific issue.

“So the consequences of incorporating resilience into our indoor air quality design means that we may add some components for increased capacity,” he said. “We also need to design — into our controls — different operating modes that are appropriate to different kinds of risk conditions, rather than simply designing for normal operation.”

“We should also talk about maintenance here,” he added. “It's a big problem that we design systems and then just let them go, to a large extent.” Not long before the pandemic, the U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO) published a report that found 41% of U.S. school districts needed to update or replace HVAC systems in at least 50% of their schools.

Click to enlarge

MISSING THE MARK WITH MAINTENANCE: Not long before the pandemic, the U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO) published a report that found 41% of U.S. school districts needed to update or replace HVAC systems in at least 50% of their schools. Simply maintaining systems will save energy as well as keep IAQ systems functioning properly. (Courtesy of ASHRAE Journal Webinar)

“Simply maintaining systems to function properly is going to save energy… so going forward, maintenance should be prioritized higher for that reason,” he cautioned, “and also because we need to keep our indoor air quality maintenance systems functioning properly as well.”