What if this constant-pressure system could maintain the same pressure on the low side of the system, no matter how much heat loading the evaporator experienced?

What if the head pressure of the system would remain constant, despite ever-changing ambient temperatures around the condenser?

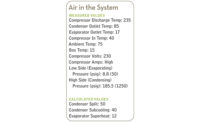

This system can become a reality if you use an automatic expansion valve (AXV) as a metering device on the low side of the system and a water-regulating valve controlling a water-cooled condenser on the high side of the system.

Let’s take a more detailed look at these components.

AUTOMATIC EXPANSION VALVE

An AXV is a metering device located between the liquid line and the evaporator. Its main function is to maintain constant pressure in the evaporator under all evaporator heat loading conditions without regard to evaporator superheat. In fact, there is no remote bulb or feedback mechanism to measure evaporator superheat. (See Figure 1.)The AXV either starves or fills the evaporator with refrigerant in response to different heat loads on the evaporator. Because of the AXV’s constant-pressure characteristics, it cannot be used with a low-pressure motor control.

The two forces that throttle the AXV opened and closed are spring and evaporator pressures. Evaporator pressure is a closing force and spring pressure is an opening force. Constant evaporator pressure is maintained by the interaction of the spring and evaporator pressures. The valve stem or adjustment screw should be adjusted for the desired evaporator pressure.

As the compressor cycles off, residual refrigerant in the evaporator boils off; this increases evaporator pressure and closes the valve.

At heavy evaporator loads, evaporation momentarily increases, causing the spring in the AXV to be compressed and throttling the valve into a more closed position. Throttling back refrigerant to the evaporator at heavy heat loads causes high superheat conditions and an inactive evaporator. (See Figure 2.)

Constant evaporator pressure is maintained, but at the cost of efficiency.

Now the evaporator’s low heat load sees more refrigerant in contact with the evaporator’s surface, and constant pressure can be maintained by the valve.

However, if the evaporator load is lowered too far without shutting the compressor off, the compressor could flood with liquid refrigerant as the valve tries to maintain its constant-pressure characteristics. In this case, the box thermostat should be adjusted to shut off the compressor before flooding occurs.

Light evaporator heat loads: At low evaporator heat loads, the evaporator pressure momentarily decreases, causing the spring force to throttle the valve more open. This maintains the valve’s constant-pressure characteristics by letting more refrigerant into the evaporator and filling out the evaporator. (See Figure 3.)

Now the evaporator’s low heat load sees more refrigerant in contact with the evaporator’s surface, and constant pressure can be maintained by the valve.

However, if the evaporator load is lowered too far without shutting the compressor off, the compressor could flood with liquid refrigerant as the valve tries to maintain its constant-pressure characteristics. In this case, the box thermostat should be adjusted to shut off the compressor before flooding occurs.

Light evaporator heat loads: At low evaporator heat loads, the evaporator pressure momentarily decreases, causing the spring force to throttle the valve more open. This maintains the valve’s constant-pressure characteristics by letting more refrigerant into the evaporator and filling out the evaporator. (See Figure 3.)

Now the evaporator’s low heat load sees more refrigerant in contact with the evaporator’s surface, and constant pressure can be maintained by the valve.

However, if the evaporator load is lowered too far without shutting the compressor off, the compressor could flood with liquid refrigerant as the valve tries to maintain its constant-pressure characteristics. In this case, the box thermostat should be adjusted to shut off the compressor before flooding occurs.

WATER-REGULATING VALVE

The water that flows through a water-cooled condenser is controlled by a water-regulating valve. (See Figure 4.) The actual location of the valve is on the water line just before the water-cooled condenser. The function of this valve is to maintain constant pressure in the condenser, despite changing evaporator heat loads or changing ambient temperatures around the condenser. The valve’s bellows are connected to the high side of the system through a capillary tube. As the refrigeration system experiences a small increase or decrease in condensing pressure, the capillary tube relays this change to a bellows it is connected to. The bellows then moves against a preset spring tension.The bellows’ pressure has an opening force on the valve; the spring has a closing force on the valve. The spring force is what the service technician sets for whatever “constant” condensing pressure is desired. This can be done with a screwdriver and pressure gage on the high side of the system.

The valve is always trying to maintain equilibrium between the spring force and the bellows force. As condensing pressure increases, the valve starts to open a little more. This lets more water through the water-cooled condenser. As condenser pressure decreases, the valve starts to throttle shut a little more, letting less water through the water-cooled condenser.

In either case, the condensing pressure is held constant at all loading conditions. When the compressor shuts off, the valve eventually shuts off all water to the water-cooled condenser because of the decreased condensing pressure during the off cycle.

The main advantage of the water-regulating valve is its ability to hold a constant condensing pressure under varying conditions. A disadvantage is that the water flow rate may be high through the water-cooled condenser if the system is under heavy loading, or if the water-cooled condenser’s tubes become fouled.

Publication date: 01/01/2002