This column will deal with the compressor, discharge line, and condenser. The July 4 column will focus on the receiver, liquid line, metering device, evaporator, and suction line. Details will be given about each component's function.

Mastering the function of each individual component can assist the technician with analytical troubleshooting skills. In the long run, this will save time and money for both technician and customer.

Compressor

Pumps refrigerant:One of the main functions of the compressor is to circulate refrigerant. Without the compressor as a refrigerant pump, refrigerant could not reach other system components to perform its heat transfer functions.Separates pressures: Another function of the compressor is to separate the high-pressure side from the low-pressure side of the refrigeration system. Since a difference in pressure is the driving potential for fluid (gas or liquid) flow, there wouldn't be any refrigerant flow without a pressure separation.

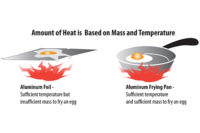

Elevates temperature: Another function of the compressor is to raise the temperature of the refrigerant vapor above the ambient (surrounding) temperature. This is accomplished by adding work - or heat of compression - to the refrigerant vapor during the compression cycle. The temperature as well as the pressure of the refrigerant is being raised.

By elevating the refrigerant temperature above the ambient temperature, heat absorbed in the evaporator and suction line - and any heat of compression generated in the compression stroke - can be rejected to this lower-temperature ambient. Most of the heat is rejected in the discharge line and condenser.

Remember, heat flows from hot to cold, and there must be a temperature difference for any heat transfer to take place. The temperature rise of the refrigerant during the compression stroke is a measure of the increased internal kinetic energy added by the compressor.

Increases density: The increase in the refrigerant vapor's pressure brings with it an increase in the density of the vapors. This helps pack the refrigerant gas molecules very tightly together and aid in the condensation or liquefaction of the refrigerant gas molecules in the condenser once the right amount of heat is rejected to the ambient. The compression of vapors during the compression stroke actually gets the vapors ready for condensation or liquefaction.

Discharge Line

Transports vapor:One function of the discharge line is to carry the high-pressure, superheated vapor from the compressor's discharge valve to the entrance of the condenser.Desuperheats: The discharge line also cools the superheated vapors (desuperheating) that the compressor has compressed. This heat is given up to the ambient (surrounding) air.

The compressed vapors contain all of the heat that the evaporator and suction line have absorbed, along with the compression stroke's heat of compression. Any generated motor winding heat may also be contained in the discharge line's refrigerant. This is why the beginning of the discharge line is the hottest part of the refrigeration system.

On hot days, when the system is under a high load and may have a dirty condenser, the discharge line can reach over 400 degrees F or more. By desuperheating the refrigerant, the vapors will be cooled to the saturation temperature of the condenser. Once the vapors reach the condensing saturation temperature for that pressure, condensation of vapor to liquid will take place, as more heat is lost.

Condenser

Desuperheats:The first passes of the condenser desuperheat the discharge line's gases even farther. This, in turn, gets the high pressure and superheated vapors coming from the discharge line even more ready for condensation, or the phase change from gas to liquid, to happen.Remember, these superheated gases must lose all of their superheat before reaching the condensing temperature for a certain condensing pressure. Once the initial passes of the condenser have rejected enough superheat, and the condensing temperature or saturation temperature has been reached, these gases are referred to as 100-percent saturated vapor. The refrigerant is said to have reached the 100-percent saturated vapor point. (See Figure 1.)

Condenses: One of the main functions of the condenser is to condense the refrigerant vapor to liquid, thus the name condenser. Condensing usually takes place in the lower two-thirds of the condenser but is system-dependent. Once the saturation or condensing temperature has been reached in the condenser and the refrigerant gas has reached 100-percent saturated vapor, condensation can take place if any more heat is removed.

As more heat is taken away from the 100-percent saturated vapor, it will force the vapor to become a liquid or condense.

When condensing, the vapor will gradually phase change to liquid until 100-percent liquid is all that remains. This phase change, or gas liquid state change, is an example of a latent heat rejection process. The phase change will happen at one temperature even though heat is being removed.

An exception to this is a near-azeotropic blend of refrigerants where there is a temperature glide or range of temperatures when phase changing.

The heat removed is latent heat, not sensible heat. This one temperature is the saturation temperature corresponding to the saturation pressure in the condenser. This pressure can be measured anywhere on the high side of the refrigeration system as long as line and valve pressure drops and losses are negligible.

Subcools: The last function of the condenser is to subcool the liquid refrigerant. Subcooling is defined as any heat taken away from 100-percent saturated liquid. Once the saturated vapor in the condenser has phase changed to saturated liquid, the 100-percent saturated liquid point has been reached. If any more heat is removed, the liquid will go through a sensible heat-rejection process and lose temperature as it loses heat.

That liquid, which is cooler than the saturated liquid in the condenser, is subcooled liquid. Subcooling is an important process because it starts to lower the liquid temperature closer to the evaporator temperature. This will reduce flash loss in the evaporator, so more of the vaporization of the liquid in the evaporator can be used for useful cooling of the load.

John Tomczyk is a professor of HVACR at Ferris State University, Big Rapids, Mich., and the author of Troubleshooting and Servicing Modern Air Conditioning & Refrigeration Systems, published by ESCO Press. To order, call 800-726-9696. Tomczyk can be reached by e-mail at tomczykj@tucker-usa.com.

Publication date: 06/06/2005